Bronze sculpture and moving image.

Cat Auburn (2022–2023), The Memoir of J F Rudd. Bronze. Size variable. Photos by Keith Hunter.

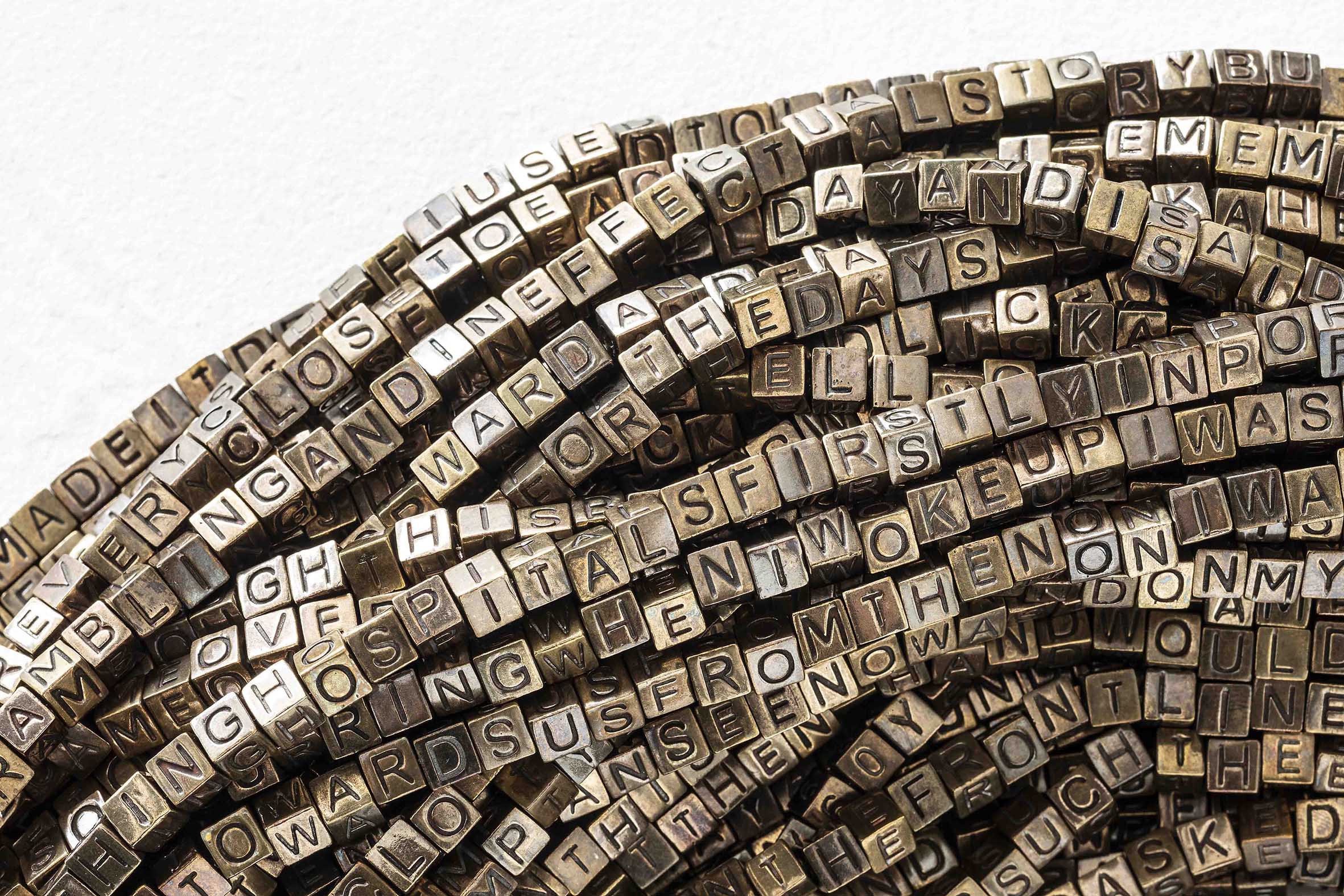

Cat Auburn (2022–2023), The Memoir of J F Rudd. Bronze (detail). Size variable. Photos by Keith Hunter.

Cat Auburn (2022–2023), The Memoir of J F Rudd. Film Still.

Cat Auburn (2022–2023), The Memoir of J F Rudd. Film Still.

Cat reimagines the Anzac legend through a paired sculpture and film, The Memoir of J. F. Rudd. These autotheoretical artworks challenging commemorative practices. In the film, we hear the artist’s voice halting read the handwritten memoir of a World War One veteran, while this same memoir is meticulously threaded with thousands of bronze beads.

Autotheory describes the practice of joining critical theory with autobiographical experience. In autotheory, thinking companions can range from those who wield institutional authority through to non-experts and those we know intimately. In The Memoir of J. F. Rudd, Cat foregrounds her autobiographic self—a self that isn’t demographically visible within the Anzac legend yet remains subject to its influence.

One of Cat’s thinking companions in this suite of artworks is Aotearoa New Zealander and Anzac WWI veteran, Lance Corporal James Foster Rudd (1891–1982):

“I first encountered Rudd through his memoir and found him to be poetic, funny, articulate, and a wonderful storyteller whom I admire. His memoir is testimony of his time in Gallipoli and then on horseback in the desert during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of WWI. When seen through the lens of the Anzac legend, Rudd’s individual memoir is part of a greater collective memory that upholds the ideals, values, and qualities of being an Aotearoa New Zealander. By virtue of his association with the Anzac legend, Rudd’s personal experiences are understood through it. By virtue of the locations in which I was raised, Aotearoa and Australia, I also understand myself through the legend, even though I don’t see myself in it. This becomes a troubled merger of individual and collective identity. It is further compounded because the Anzacs are not seen as individuals but as a “collective entity”[1] into which Rudd’s distinctiveness is compressed.”

Cat explores this complicated weaving of individual and collective identity through the suite of artworks, The Memoir of J. F. Rudd. She co-centres her own and Rudd’s experiences with the Anzac legend through artistic practices such as threading beads, narrating, self-filming, swimming, and bronze casting. These artistic practices aim to disrupt the prevailing heroic narrative of the Anzac legend, in a shift away from what, in her essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin terms the “killer story.” In her essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Le Guin critiques the traditional narrative of the hero’s journey that predominates in Western literature as limited and patriarchal. Instead, Le Guin advocates for narratives that encompass more than conflict and violence. She offers a narrative counterpoint that makes room for “the life story” in the metaphorical form of “carrier bag/belly/box/house/medicine bundle.” In thinking-with Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory, Cat explores the stakes of questioning the centrality of military heroism within Aotearoa’s collective identity, repositioning the socio-political history invoked in The Memoir of J. F. Rudd as part of an evolving discourse rather than as a reinscription of a glorified military past within the present.

Cat engaged with traditional commemorative languages by threading Rudd’s memoir with thousands of bronze alphabet beads onto a fifty-two-meter-long continuous string. In contrast to war re-enactors, whose actions are based in the repetition of militaristic actions, Cat’s artistic process is rooted in the traditions of crafting and storytelling. This act of threading not only physically reenacts Rudd’s memories and narratives but also interlaces Cat’s own experience with Rudd’s memoir. Cat’s use of repetition reimagines the traditional concept of commemorative reenactment, providing a counterpoint to the simplifying tendencies of nostalgia so beloved of war reenactors.

Another of Cat’s thinking-companions in The Memoir of J. F. Rudd is bronze – a material associated with commemorative monuments. Often mired in controversy for their selective historical representation and the socioeconomic power dynamics they reflect, commemorative monuments are cultural artefacts that enable the transference of national ideals to future generations:

“By casting my autobiographic, intimate, everyday actions into bronze on a domestic scale, I commemorate my intention to engage with the Anzac legend through a new lens. This act challenges the institutional frameworks of collective remembering (and forgetting) that play into the instrumentalization of Anzac narratives for national identity, thereby troubling these frameworks in a manner that echoes Le Guin’s proposition of the carrier bag as a tool for storytelling.”

In this way, Cat shifts the focus of the Anzac narrative from that of conflict, violence, conquering, or being conquered to storytelling as a process of ongoing change and development.

[1] Jed Donoghue and Bruce Tranter, “The Anzacs: Military influences on Australian identity,” Journal of Sociology 51, no. 3 (2015): 451.