The Horses Stayed Behind is a WW1 Centenary project by Cat Auburn, and the entry point for a deep line of research within her art practice. The project’s development and realisation was supported by the Tylee Cottage Artist Residency (2014/15), The Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui (NZ) and funded by Creative New Zealand. The Horses Stayed Behind was the winner of the Best Regional Exhibition Award at the 2016 New Zealand Museum Awards and has been exhibited at the following venues between 2015 – 2018:

The Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui (NZ), SCAPE Public Art Christchurch (NZ), Te Manawa Museuam of Art, Science and History Palmerston North (NZ), Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato (NZ), Tauranga Art Gallery (NZ).

What you will find on this page: ‘The Horses Stayed Behind’ essay by Sarah McClintock; the Sarjeant Gallery Podcast episode on ‘The Horses Stayed Behind’; a video of ‘The Horses Stayed Behind’ installed at Tauranga Art Gallery, and images from the development and subsequent installations of the project. For an Art News article on the project please visit here. Two watch to an artist about the project talk please visit this journal entry.

THE HORSES STAYED BEHIND

Cat Auburn, 2015. ‘The Horses Stayed Behind (detail)’. horse hair, copper, linen.

National Army Museum Te Mata Toa. Accession Number: 2008.41, Albert Crum Collection. ‘Shooting wounded horse‘, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage).

The following text is an essay written by New Zealand curator, Sarah McClintock to accompany the touring exhibition.

It has been a hundred years since 100,000 New Zealand men and women left the shores of Aotearoa to serve on the battlefields of World War One. Over the four years marking the centenary of this war, projects from across the country are being launched to commemorate the sacrifices made by this generation. A story that has come to light and gained more recognition is that of the war horses. Ten thousand horses left New Zealand for the front lines in World War One, but only four returned.

These riding mounts and pack horses were sent to Europe, the Middle East and the Pacific as essential assets in the fighting of this Great War. The horses were purchased or donated by members of the public and their bond with the soldiers was strong. However, at the conclusion of the war with severe transport shortages and fear of diseases, it was decided by the Government that those that had survived would not be transported back to New Zealand. Instead they were redistributed to remaining forces, sold to locals, or destroyed. Many soldiers, believing that it was in the best interest of their mounts, had their horses deemed unfit and killed instead of leaving them behind. It is easy to see correlations between the way the soldiers were regarded by those in command being reflected in the way the horses were treated. Horses and men alike were viewed as resources, their usefulness in battle was considered as paramount. Each was judged on age and fitness to gauge their effectiveness as pawns on the chessboard of geo-politic battle.

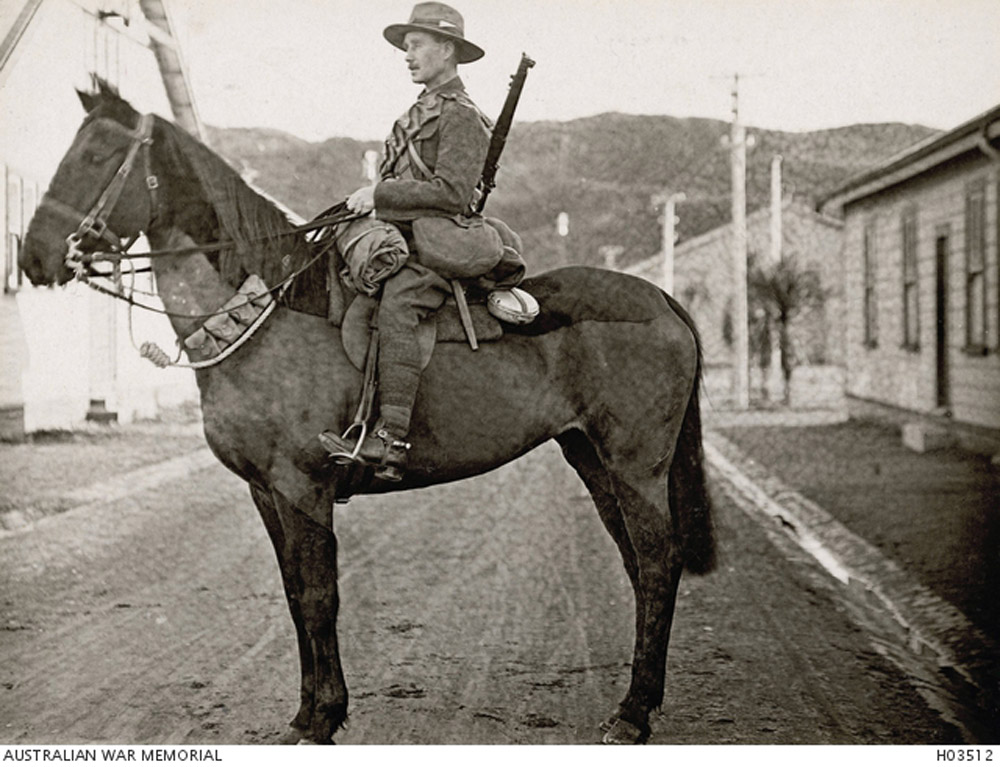

Photo of A New Zealand mounted rifleman with full equipment during First World War, 1914-1918. The horse he is riding is ‘Bess’, mount of Colonel Guy Powles, one of only four horses to return to New Zealand after WW1 (1920). Photo: Collection of Australian War Memorial. Accession Number H03512.

Cat Auburn came to Whanganui to be artist-in-residence at Tylee Cottage from November 2014 to February 2015 and is well versed in the use of animals as proxies. Her sculptural work has used various animal forms to represent ideas of fragility, identity and fear. Auburn taps into the art historical use of animals as metaphor, i.e. dogs have signified loyalty, cats translate to cunning and horses signal power and glory. Auburn recognises the use of animals in art can be a form of short hand in expressing common ideas and attributes and that this understanding gives her the power to disrupt these tropes. For her residency in Whanganui Auburn built on her history of engaging with animal narratives by commemorating the lost war horses with horse hair rosettes: flowers made in the style of Victorian hair wreaths.

The Victorian fascination with the macabre finds its roots in the forty years of public mourning undertaken by Queen Victoria after the death of her husband. With grief made popular by the monarch, who after Albert’s demise wore black for the rest of her life, death became an everyday part of nineteenth century life. Mementos mori were carefully woven out of the hair of the deceased, these were then turned into items of jewellery or added to family or community hair wreaths. During the early twentieth century, as World War One raged, these wreaths were likely still hanging on the walls of family homes. The method of weaving the hair, a technique now largely lost, had to be resurrected by Auburn from one hundred year old texts, as she created something beautiful with this potentially disturbing material.

Cat Auburn, 2015. ‘The Horses Stayed Behind (detail)’. horse hair, copper, linen.

Auburn’s decision to use hair for this work was not simply a reference to the technique she employed. Hair is intimate, it grows from us and for many it is closely tied with identity. We use our hair to indicate our sexual and social alignments: undercuts, mohawks, mullets and moustaches each act as stereotypes that can be used to signal to the world our inner selves. Hair can also hold secrets, stories and myths: the Biblical Sampson held his power in his hair, apocryphal stories circulate about hair continuing to grow after death, and a common sign of the excesses of Louis XVI’s French court is the elaborate dioramas that adorned Marie Antoinette’s hair and the nineteenth century art critic John Ruskin was said to be so shocked to see body hair on his new wife that the marriage remained unconsummated until their scandalous annulment. It should be benign but hair is loaded with meaning, some of it unsettling. Hair, like war, has the power to attract and repel.

Once the connection between horses, war and hair made, the question became: how to collect the hundreds of horse hair locks that would result in a fitting memorial work? It was important for Auburn to connect with the community that would, one hundred years ago, have been supplying the military with horses. Growing up in rural Northland, Auburn spent her days riding and competing at agricultural and pastoral shows. So in late 2014, armed with scissors, plastic bags, permanent markers, and a script, Auburn revisited her youth and attended A&P shows across the lower North Island and as far away as Canterbury. With a strong social media presence, and no small amount of charm the artist told the story of the horses that left New Zealand for the war, the sacrifices they made, and asked horse owners from across the country to make a small sacrifice of their own: to donate a small clipping of full length hair from their horse or pony’s tail. The response was overwhelmingly positive and the support of the community in bringing in donations has been essential to the success of the final work.

Cat Auburn collecting donations of horsetail hair from Rachel Forrester’s police horse, Belle at the Stratford A&P Show (NZ) 2015. Photo: Sarah McClintock.

Examples of horse hair donations in their raw state. Photo: Cat Auburn.

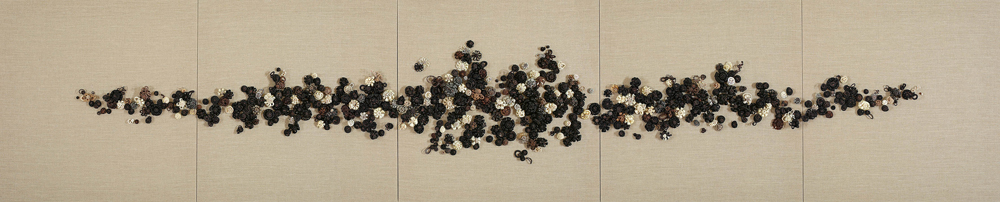

Rather than creating a figurative motif or picture with the five hundred resulting rosettes Auburn has instead chosen to present them using a formalist aesthetic. Like a heartbeat stretched across five linen canvases the horizontal arrangement, devoid of narrative, allows each unique flower to hold onto its individuality while maintaining a role within the larger group. Each horse and rider is identifiable, in stark contrast to the anonymous fate that awaited thousands of the horses and men who left New Zealand for the war.

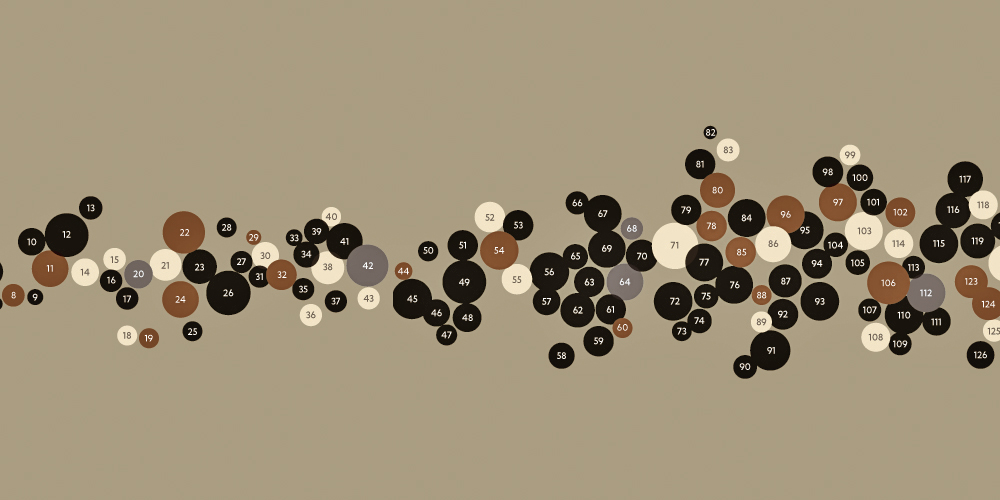

Detail from an infographic map designed by Joseph Salmon to locate the individual horses within the finished artwork.

The making of the horse hair rosettes was a ritualistic act. Every donation was put through the same process: washing, sterilisation, drying, sorting, weaving with copper wire, working into a flower, and finally stitched onto the linen canvases. Almost regimental in the making of the work, Auburn’s approach reflects the importance of the ceremonial when remembering and memorialising, particularly when it comes to death. The rituals of mourning change across cultures, but we all have them: funerals/tangi, wearing black, and the cutting of hair are just some of the formalities we go through when someone dies. The reason for each act it not only to mark the life of the person who has gone, but to comfort those left behind.

Every donation of full length horse tail came to Auburn with a story. Some with small notes of support, others with cherished photographs and heartrending tales of riders and horses that have passed away. The cathartic nature of this project has gone well beyond the memorialisation of the World War One horses and has become an active way for members of the riding community to pay tribute to their colleagues, horses and ponies. This type of mourning, a multisensory way of expressing grief is a central part of The Horses Stayed Behind. Long forgotten events and memories of loved ones can be triggered by a smell, taste and sound. The final form the rosettes take across the canvases not only resembles a heartbeat but also an isolated audio track. The horses and riders from the past and present join together in this work with a voice that speaks of collective mourning and loss.

Cat Auburn, 2015. ‘The Horses Stayed Behind’. horse hair, copper, linen.

Cat Auburn, 2015. ‘The Horses Stayed Behind (detail)’. horse hair, copper, linen.

Through the rosettes Auburn subverts the customary memorialisation of war, complicating the heroic glory inherent in large scale bronze and marble statuary. These very serious and dour sculptures off a two dimensional view of history at best: the conqueror standing tall surveying his dominion. This interpretation of history is destabilised by Auburn on multiple levels. The first being the flipping of the story from vertical to horizontal with the five metre long canvas. Traditional war memorials are often towering figures and structures that loom over the viewer. Auburn gives her commemorative work a human scale by placing the horse hair rosettes along a horizontal axis. We can view the work at our own level, seeing its detail and complexity.

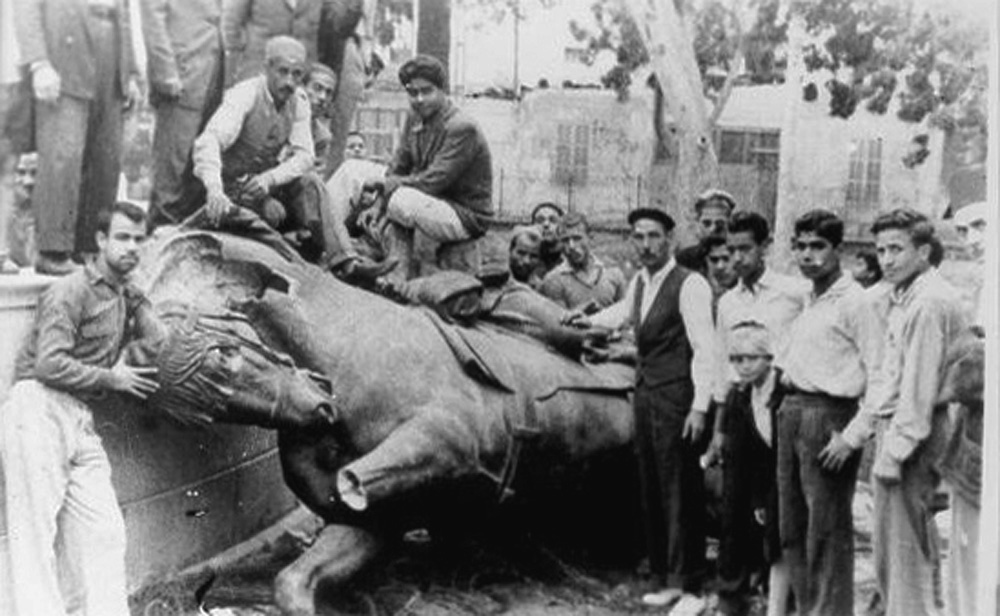

Auburn’s interest in the manipulation of history through public art is made explicit in the display of a fragment from the bronze memorial to the ANZAC Mounted Rifles, Camel Corps and the Desert Mounted Corps which was erected in Port Said in 1932. The monument was destroyed in the 1956 Suez conflict and one of heads from the horses depicted is now on display at the Australian War Memorial. The original sculpture portrayed two ANZAC mounted soldiers: one an Australian and the other a New Zealander. Shown as colleagues and equals heading into battle, the message of the monument shifted significantly after it was destroyed and remade in Australia. The new monument, of which two were made, shows an Australian Light Horseman coming to the aid of the New Zealand Mounted Rifleman. The re-contextualisation of the monument is indicative of the casual ways in which history can be changed over time. This fragment, on loan for the exhibition from the Australian War Memorial, is minute. So small when compared to the massive sculpture form which it originated. Its inclusion confronts the fact that public memory and our collective understanding of history is often placed within these giant bronze monuments that have little relation to actual events.

‘Egypt. Port Said & canal zone. Port Said, the Anzac War Memorial‘, [between 1934 and 1939]. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-matpc-22334. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. USA .

Photo: The destruction of the ANZAC Mounted Rifles, Camel Corps and the Desert Mounted Corps Memorial Monument in Port Said – 1956. Source: Unknown. The artist would be very grateful to have more information on the provenance of this image.

The horse hair oud made for this exhibition is a Middle Eastern string instrument not unlike a lute and acts as a nod to another side of the World War One story. In the recent commemorations surrounding the centenary of World War One the impact of war on the allied troops is fundamental to the stories we are told. Understandably one aspect of war often forgotten is the effect the events had on the ‘enemy’. Almost twice as many Ottoman Turk and Arab soldiers were killed or wounded at Gallipoli when compared with the Allied casualties.[1] Auburn wants us to consider that each of these enemy combatants were as much victims as the New Zealanders who were injured or lost their lives. The tone of the oud, sorrowful to Western ears, acts as an aural link to the feelings of loss. It is for this reason that Auburn worked with a UK-based luthier to make the oud utilising some of the donated horse hair.

Cat Auburn, 2015. ‘The Horses Stayed Behind (oud)’. horse hair, resin, NZ timber. To see the construction of the oud please visit this post by Steve Evans of Beltona Resonators.

Auburn is conscious of the role gender plays in the telling of these stories. She wants to open up the ways in which we commemorate events that have impacted in the nation as a whole. By using a craft-based medium, primarily undertaken by woman to represent the traditionally masculine domain of war, Auburn asks the viewer to consider an expanded approach to memorialisation. Do all war memorials need to be statues? Can we not adopt a more inclusive way of remembering? This interest in communal memory making is emblematic of the collaborative way the work was made. Auburn has consciously referred to the work as a project throughout its development. Art often brings to mind the artist working independently on a singular work, what Auburn has done with The Horses Stayed Behind is bring her vision to a community who have rallied around to help her create the final piece.

The Horses Stayed Behind deals with complicated ideas in a gentle way. Auburn takes our hand and leads us through a complex and layered way of understanding grief, memory and time.

Text by Sarah McClintock.

[1] ‘Gallipoli’ http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/interactive/gallipoli-casualties-country