‘Looking Up to You’ is a collaboration between Cat Auburn and celebrated New Zealand photographer, Fiona Pardington. The project was commissioned by Wellington City Council for the Courtenay Place Light Box Project in the summer of 2012/13.

Artworks from ‘Looking Up to You’ also featured in the group exhibition, ‘After You’, at Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare O Rehua, Whanganui, NZ, 2013. View ‘After You’ here.

What you will find on this page: selected images from the exhibition; images of the completed installation; an essay by Andrew Paul Wood, originally published on EyeContact’s website here. All studio photography for Cat Auburn’s final images in ‘Looking Up to You’ was taken by Steve Unwin Photography.

‘Looking Up to You’ – The Courtenay Place Light Box Project

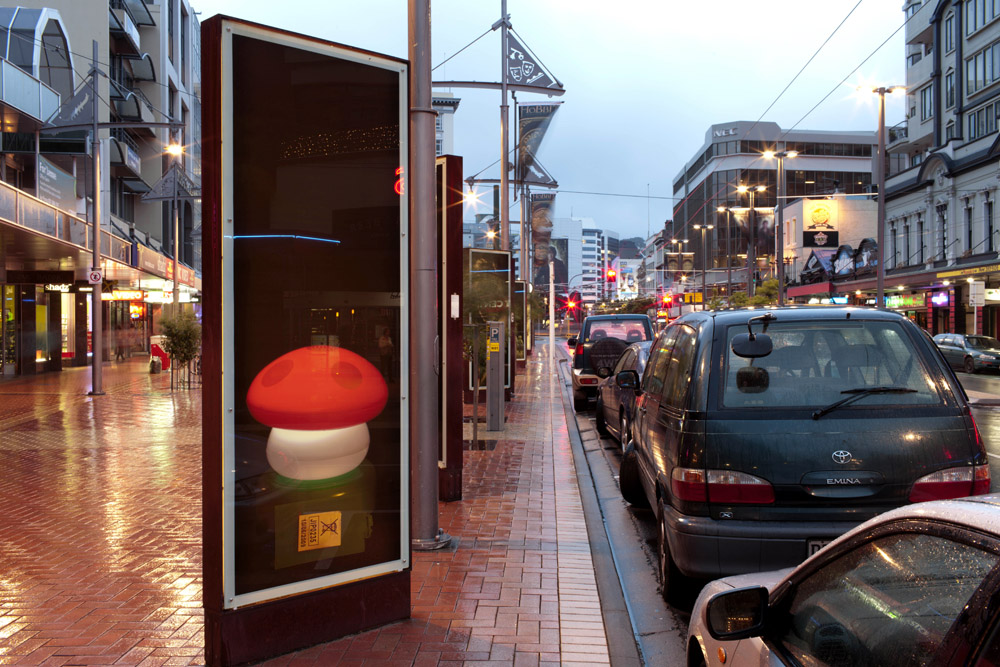

Cat Auburn and Fiona Pardington, ‘Looking Up to You’ installation (2012). photo credit: Wellington City Council

Cat Auburn and Fiona Pardington, ‘Looking Up to You’ installation (2012). photo credit: Wellington City Council

A selection of final photographs from ‘Looking up to You’ and the artworks that inspired them.

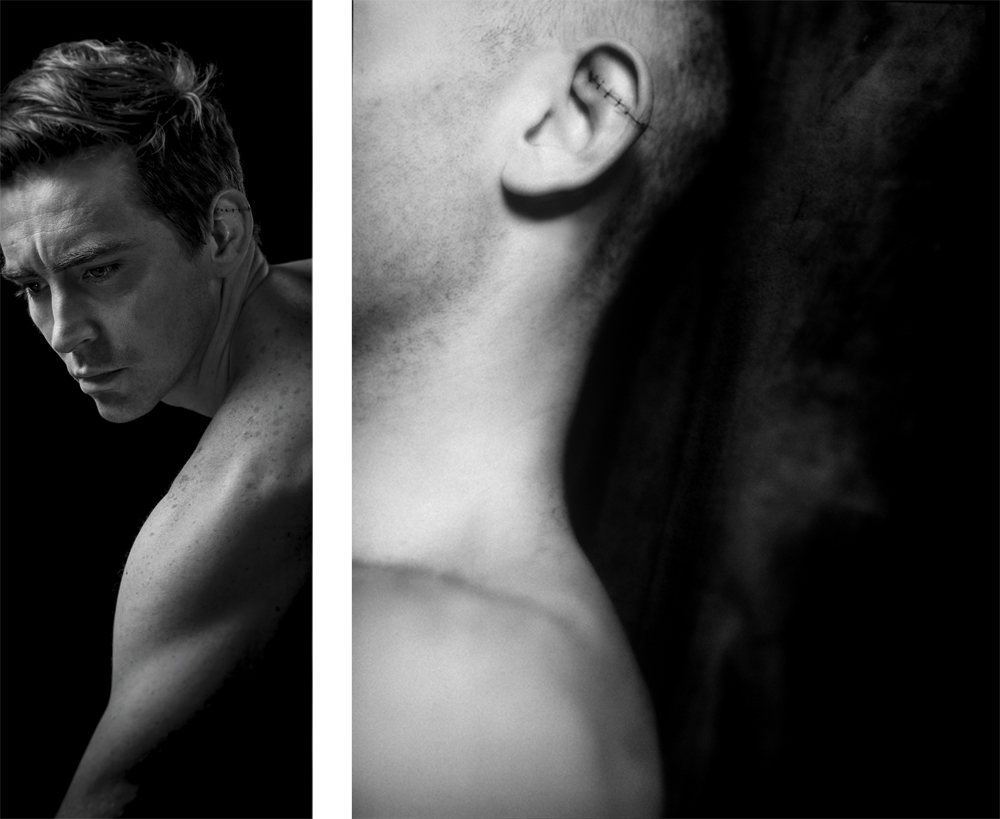

Left: Cat Auburn (2012), ‘Portrait of Lee Pace as Proud Flesh’. Right: Fiona Pardington (1997), ‘Proud Flesh’.

Left: Cat Auburn (2007), ‘Chalfont Candyman’, resin,brass. Right: Fiona Pardington (2012), ‘Dead Leaves, Bird Skulls and Candied Apple, Leigh’.

Left: Fiona Pardington (2011), ‘Still Life with Seaweed and Lemons’. Center: Work-in-progress, Auburn’s sculptural version of Pardington’s photograph. Right: Cat Auburn (2012), ‘After Still Life with Seaweed and Lemons’.

The following text is an essay written by New Zealand writer, Andrew Paul Wood. This essay was commissioned by the artists and Wellington City Council as a collaborative part of ‘Looking Up to You’.

It is difficult to imagine two artists with more different practices working together than Wellington-based Cat Auburn and Auckland-based Fiona Pardington. Auburn is a young emerging artist best known for her sculptural practice, while Pardington is one of New Zealand’s most distinguished photographers. While it is perfectly natural for a younger artist to be inspired by an established artist and perhaps allude to or imitate them in homage, it is more unusual in the modern era for this to become the basis of a significant project, and even less usual for it to result in a collaboration of such compelling synergy. Just as the photograph once borrowed from the aesthetics of painting for added authority and authenticity, in the contemporary context photography borrows light boxes from advertising and marketing.

So anomalous is Pardington and Auburn’s Looking Up to You that I struggle to find a structure in which to easily talk about it, so I will resort to the classics. Philostratus the Elder was a Greek author who flourished in the third century and one of his most famous works was the Imagines (or Images), a collection of short essays ostensibly describing sixty-four mostly mythologically themed paintings, supposedly seen by him in Naples but also quite possibly entirely fictional, in poetic detail or ekphrasis. The entire work is framed in terms of explaining art, its symbols and meaning, to a ten-year-old boy. Consider Courtney Place as a grand outdoor gallery, primed to lure the eye of even the most jaded flâneur on their Passeggiata.

Let us begin with an image Pardington has created a still life using an object from Auburn’s childhood – a small ceramic cat that at some point has been broken and glued back together. The cat is a caricature, facsimile (twice over as a photograph) of the living, breathing domestic house cat, the scaled down, softened and civilised version of the King of Beasts, the lion. The presence of cats is also a punning play on Auburn’s first name. Looking Up to You is full of such rhizomatic interplays. It suggests something of Wittgenstein’s dilemma regarding the limits of communication – all language is contingent. What we think we understand is meant by an utterance or iteration will never exactly match the original concept.

The cat finds an echo in another image of one of the favourite designs proposed for the New Zealand coat of arms in 1908 following the granting of official Dominion status. The shield has two supporters, a British lion and a creature with the top half of a horse and the bottom half of a fish is called a hippocampus – the seahorse. Confusingly it is also the name of the seahorse-shaped part of the brain heavily involved with memory. This has a rather startling frisson with the photograph of a maquette for a sculpture Auburn conceived before she ever knew of this coat of arms – an unprecedented chimera half horse and half lion. The only mythological creature that comes close is the hippogryph – part horse, part lion and part eagle, supposedly the offspring of a griffin and a mare.

Auburn’s After ‘Still Life with Dying Purple Dahlia’ is a re-creation, or perhaps a kind of Baudrillardian facsimile of Pardington’s still life photograph Still Life with Dying Purple Dahlia. While Pardington’s original is full of objects that possess personal significance peculiar to the photographer, Auburn captures some of the aura of authenticity by sourcing her replacement objects in season in Wellington; the lilies from her local dairy, the tamarillo from Mirimar New World. The same scenario applies to After ‘Still Life with Dahlia’, Sand and Takahikare Wings. In Eiffel Tower, Gorse, Rhinestones, Auburn uses objects that Fiona gave to Cat from her past still life photographs, including the Eiffel Tower souvenir trinket. Auburn’s use of gorse alludes to both Pardington’s interest in using the plant in future, but also to the Wellington site where Auburn rides her horse and sourced the gorse.

The autobiographical allusions are by no means exclusive. Auburn feels perfectly at liberty to place some ironical aesthetic distance between herself and Pardington as well. For example, Auburn responds to a still life photograph of a wax and plaster fungus from Pardington’s The Champignons Barla series with her own photographic still life of a plastic air freshener in the shape of a mushroom. The evident ironic humour lifts the interaction above the level of merely an homage, to something approaching a cheeky challenge with a solitary Magic Mushroom. It is a masterful illustration of semiotics in action, raising a multitude of questions regarding authorship, appropriation and interpretation. One is reminded a little of Jorge Luis Borges 1939 short story Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote in which the fictional author of the title attempts to re-create line by line the entirety of Cervantes famous picaresque novel.

Context and creators also find their way in. Auburn incorporates Pardington herself in a fetching photographic portrait of the artist based on Pardington’s 1996-2001 series One Night of Love. And while still on the subject of portraits, the city of Wellington itself makes an appearance – a sort of mise-en-abyme recursion, the city within the city – in the form of two historical photographs from the Wellington City Archives: 1920s, Wellington City Council Rest Rooms for Women and Children, Manners Street (A 8479) and an image from 1910 of Courtenay Place, looking west (Tourist Series 2357). Courtenay Place becomes an art gallery, a narrative, a bestiary of imaginary creatures, and a dipping into the encyclopaedias of two oeuvres. The work is completely context specific – it could not exist and be meaningful anywhere else.

Andrew Paul Wood, 2012