Cat Auburn completed the final year of a Master of Fine Art (distinction) in the 2015/2016 academic year at the BxNU Institute, a unique postgraduate course delivered by Northumbria University in partnership with BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art (UK). This program culminated in a group graduate exhibition, There Were Islands, at Baltic 39 in June 2016. A limited edition archival box was also developed as an alternative to the traditional MFA ‘catalogue’; it has since been inducted into many international collections, including the Tate Library and Archive.

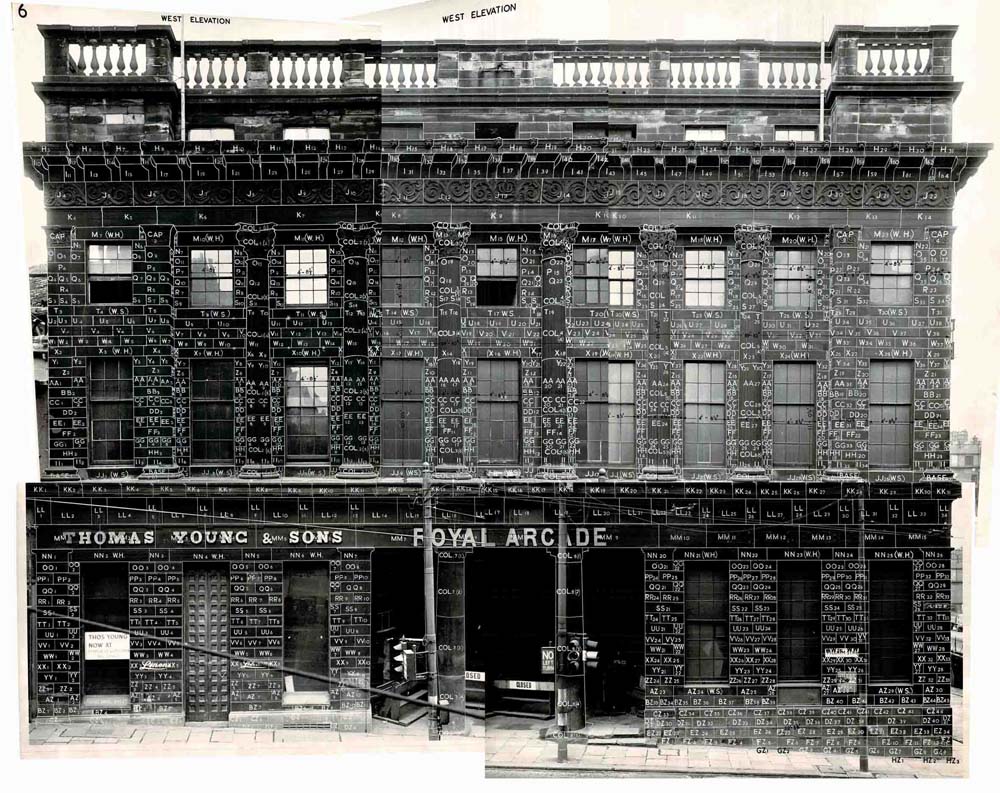

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, digital photograph, 3m x 2.5m. Source: The Tyne and Wear Archives.

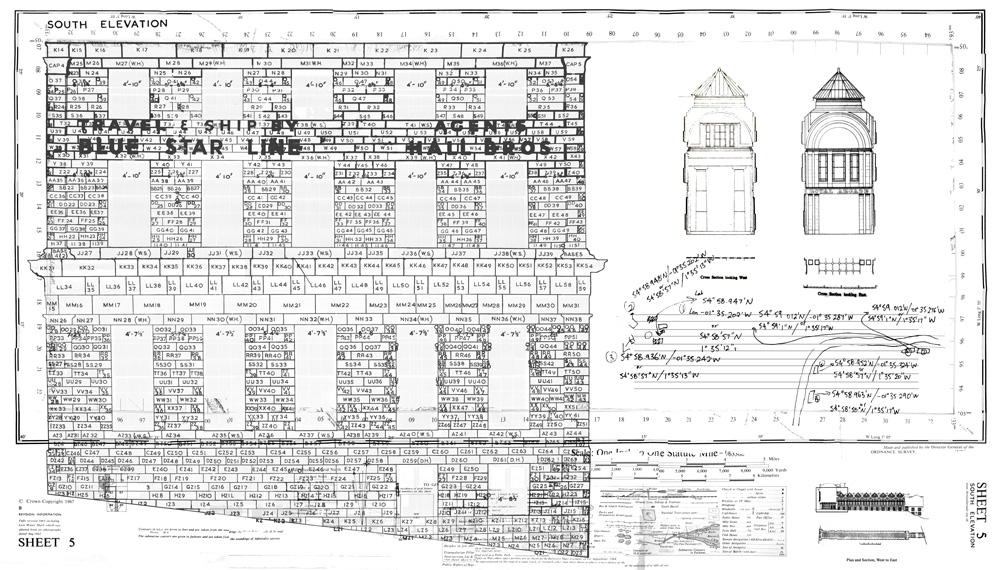

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967 – Ordnance Survey Sheet #5, 1000 x 570mm.

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967 – Ordnance Survey Sheet #5, 1000 x 570mm.

I engage with sociological, historical and economic hyperobjects[1]: events that are too vast for an individual to wholly grasp and experience. Within my practice these hyperobjects are encountered through the fractured prism of particular subject matters, such as a public memorial or, in the case of this postgraduate project, a demolished building. What lies at the heart of my interdisciplinary way of working is a keen interest in issues of authenticity coupled with a desire to interrogate and make visible the complicated systems and invisible structures that surround us all.

An example of this is a project I developed during the MFA program at the BxNU Institute called Condition Report 1967, spanning film, photography, sculpture and a permanent public installation. The project concerns a building called the Royal Arcade (1832-1963), the only Grainger/Dobson building to be destroyed in Newcastle Upon Tyne and a significant example of the Tyneside Classical style architecture unique to the city. The Royal Arcade was also one of few remaining historical arcades in the United Kingdom at a time when the population was protesting the impact of subtopia[2] – postwar urban sprawl and the perceived ‘invasion’ of modern, high-density architecture.

Site of the demolished Royal Arcade. Swan House, corner of Mosley and Pilgrim Street, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK.

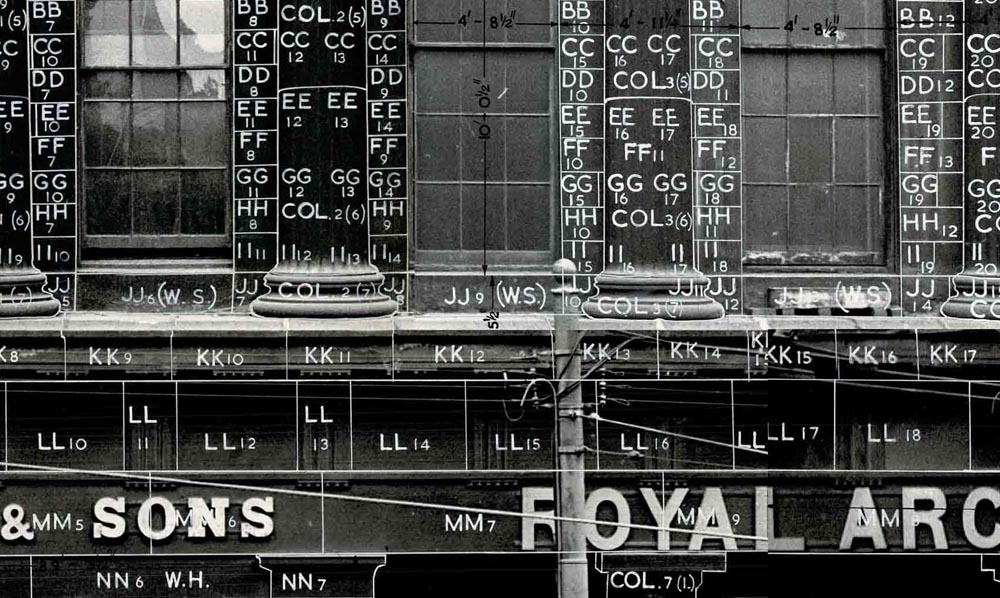

The Royal Arcade was demolished in 1963 to make way for a giant roundabout at the heart of a new motorway bypass. This town planning was widely condemned because not only did the bypass erase an important piece of architecture, it physically split the city in two. In what I suspect was a diversionary compromise, local officials promised to reassemble the façade of the Royal Arcade close to its original site, adorning the front of Swan House, an enormous modern building to be constructed in concrete. The stones of the façade were carefully numbered (see fig. 1 & 3), dismantled and stored, whilst a replica of the arcade’s internal promenade was purpose built inside Swan House – visitors would pass through the original façade into a concrete and plaster ‘pastiche’ of the arcade. The motorway bypass and Swan House were completed by 1971, as was the interior arcade, but the façade was never reconstructed. All that is left of the Royal Arcade is an anachronistic promenade floating forgotten inside a concrete shell, and rumours ofa grand building, painted with numbers and buried for safe keeping, waiting for future generations to dig up[3].

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967 (detail), digital photograph, 3m x 2.5m. Source: The Tyne and Wear Archives.

The stones of the Royal Arcade seemingly disappeared; the official reasons given for abandoning the reconstruction, such as irreparable damage to the masonry and even the accidental removal of the numbering system on the stones cannot be substantiated, in fact there is more evidence to refute these claims than not. This era was notorious for political corruption, particularly in the North East, and very little reliable source material, either paperwork or stonemasonry, remains of the Royal Arcade. There are also many urban legends surrounding the building that muddy the waters. For example, when working with the Geography Department at Northumbria University and following several grey-archaeological leads, we were able to determine where the bulk of the building isn’t by using ground penetrating radar. Over the course of this project I have identified eighteen pieces of the original masonry spread throughout local parks as ornamental follies; their provenance is largely unknown to the public and the location of the bulk of the masonry is still open to debate.

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, film still (27 mins). 1971 Replica of the Royal Arcade inside Swan House.

Condition Report 1967 is a project of several parts or measures; much like the scattered fragments of the Royal Arcade, they can never truly articulate the whole that they reference. One such part is a film that condenses the various sites of the Royal Arcade into one location onscreen. Images of moss-covered columns in a winter-bare park are interlaced with the arcade replica in its current incarnation as a Thai restaurant. This imagery is coupled with the crisp BBC narration of a 1967 document from the Tyne and Wear Archives[4] citing the condition of each stone.

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, film (27 mins).

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, film (27 mins). Installation image, There Were Islands.

On another floor of the gallery the viewer is dwarfed by a large photograph: a tessellated image of the West Façade of the Royal Arcade. It is a composite of smaller images digitally stitched together to reveal the entire façade laid over with a curious periodic table-like grid. These previously unseen black and white photographs were misfiled in the Tyne and Wear Archives sometime in the 1970s and show sections of the Royal Arcade pre-demolition with an index manually drawn over the top of each photograph – an era-specific map to guide the reconstruction of the façade.

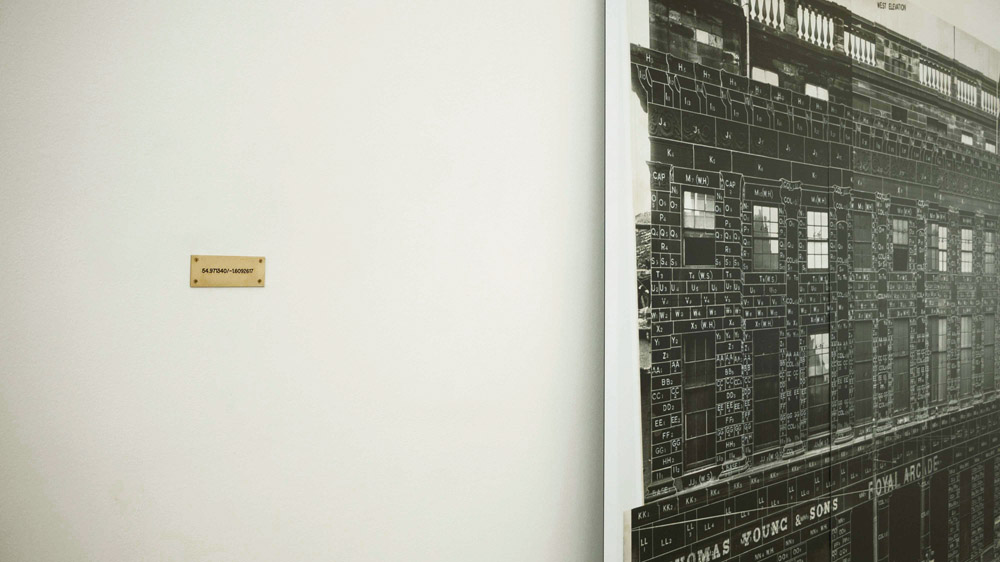

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, installation image (gallery).

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, installation image (gallery).

The photograph is encountered though another grid-like structure: a heavy plaster column suspended fractionally above the ground in a white safety net. The net is ubiquitous, it syphons audiences through the gallery, simultaneously framing and infiltrating other artworks in the exhibition with a white grid pattern. Its structure is reminiscent of a vortex-shaped graph and suggests systems of measurement used to visualise phenomena that are impossible to experience. The column is a plaster cast taken from one of the original pieces of Royal Arcade stonemasonry found in Heaton Park. Since architectural plans of the building are non-existent, as is the majority of the stonemasonry, the index system featured in the large photograph is redundant as a unit of measure. The plaster cast is a 1:1 facsimile, providing a key to the original building’s dimensions and offering a control for the project when no other true measurements are available.

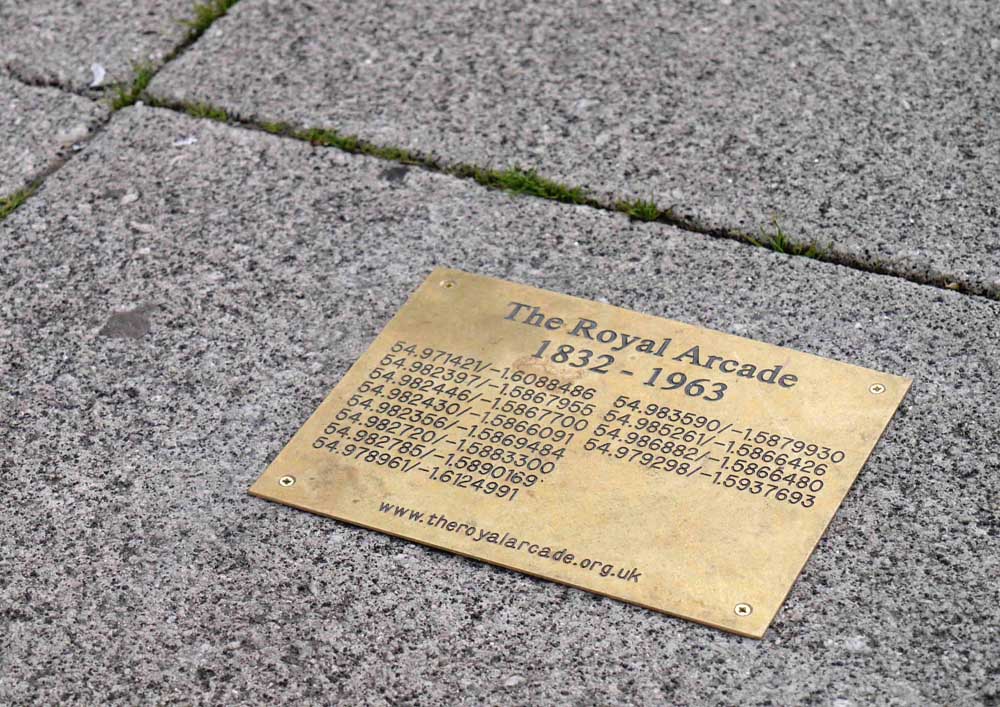

The final piece of Condition Report 1967 begins as a small brass plaque situated discreetly within the gallery space; the engraved gps coordinates invite viewers to visit an offsite location two blocks from the gallery. Another brass plaque is permanently installed in the footpath at this location, naming The Royal Arcade, the dates it stood on the site and a website. It also lists the gps coordinates for finding the remaining pieces of stonemasonry and other sites significant to the building, whilst leaving room for more coordinates to be added in the future. This is a permanent installation in agreement with Newcastle City Council, and I am currently in negotiation with the Tyne and Wear Building Preservation Society to hand over the guardianship of the plaque and website to ensure their relevance to the public and the city in perpetuity.

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, brass plaque, 76 x 127mm

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, installation image.

Cat Auburn (2016), Condition Report 1967, brass plaque, installation image. Permanent installation outside Swan House, corner of Mosley and Pilgrim Street, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK.

Condition Report 1967 is framed by a particular set of sociological conditions and ponders endemic obscurification within political policymaking. Through tracking the history and locations of the few remaining stones, the Royal Arcade has become an indexical matrix through which to observe larger administrative mechanisms that continue to shape the international political landscape to this day. The empirical, investigative approach taken in Condition Report 1967 belies the crux of the project; the discovery of the Royal Arcade’s final resting place was always understood to be a farfetched possibility. There are no definitive truths to reveal to an audience due to the opaque conditions already outlined. Instead, this project offers a spectrum of authenticity for the viewer to position themselves within.

[1] World War One, colonialism and global warming are all examples of hyperobjects as explained by Timothy Morton (2013) in Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[2] The Man Who Fought the Planners the Story of Ian Nairn (2014). Director, Kate Misrahi.

[3] Conversation with Peter Livsey, 14 January 2016, during a field trip in Newcastle Upon Tyne city centre.

[4] (1962-1969) Newcastle, Royal Arcade (Pilgrim Street development), Tyne and Wear Archives. DT.CC/128. Newcastle.