A collaboration between Cat Auburn and fellow New Zealand artist, Estella Castle.

To commemorate the 200th anniversary of Constable’s time in Suffolk, Auburn and Castle traveled to Constable Country to re-stage his iconic British painting, ‘The Hay Wain’ at the original National Trust site in Suffolk on which the painting is based. The title of the project takes its name from a book about Suffolk rural life by George Ewart Evans.

The first part of this project was the live public staging of the recreation on 4th September 2016, involving the local community. The second part is a moving image artwork that uses footage from the event interwoven with archival colonial re-enactment imagery from New Zealand. Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay explores a vision of historical New Zealand as exported through Britain’s cultural lens. This exploration focuses on narratives of authenticity within heritage institutions and art history at large.

Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay has been shown in the following exhibitions between 2016 – 2017: The River Lie, The Suter Gallery, Nelson, NZ; Post Landscape, Bartley + Company Art, Wellington, NZ; Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay, Flatford Mill, National Trust, Suffolk, UK.

What you will find on this page: ‘Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay’ essay by Sarah McClintock; a radio interview with Cat Auburn and Sarah McClintock on RNZ, a radio interview with Estella Castle on BBC Suffolk (UK); images from the live event at Flatford Mill and the subsequent moving image work created by Auburn and Castle. A video from local UK new outlet about the live event can be seen here. The exhibition catalgue for The River Lie exhibition can be found at The Suter Gallery website here.

Cat Auburn & Estella Castle (2016). Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay. trailer

Cat Auburn & Estella Castle (2016). Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay. film still

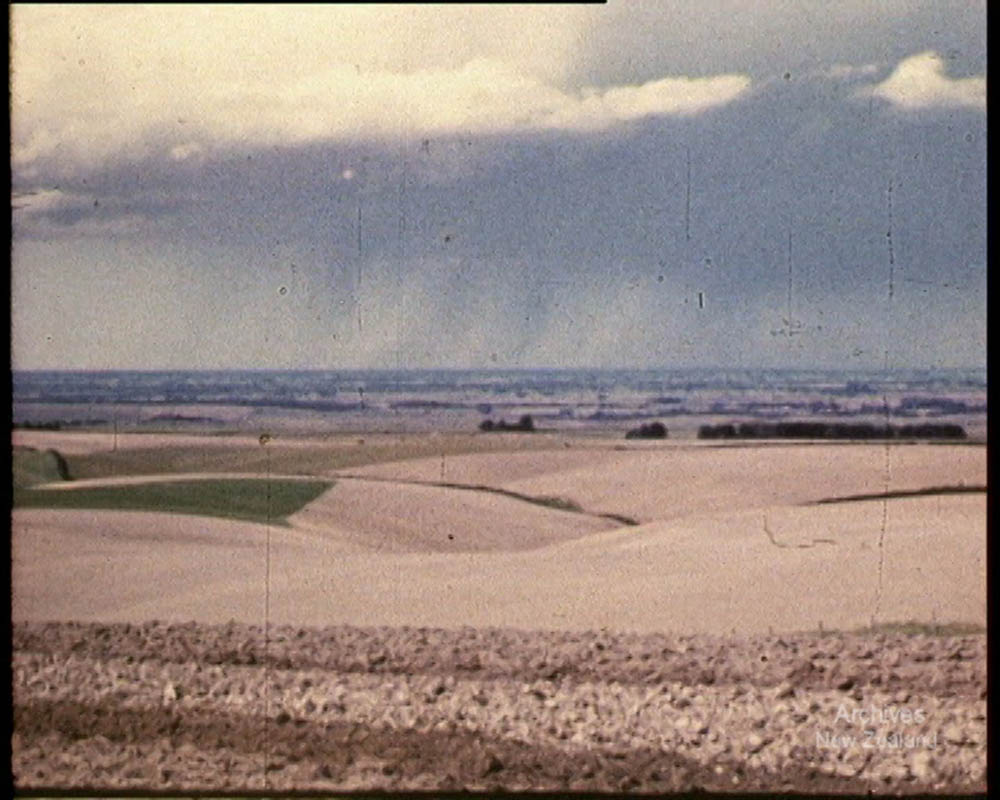

Canterbury is 100, film still, photo credit: Archives New Zealand

Harry Bonne Smith (Happy Smith) circa 1970, New Zealand. Courtesy of the Smith Family.

Cat Auburn & Estella Castle (2016). Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay. film still

Re-enactment of The Hay Wain at Flatford Mill, Suffolk. N&J Heavy Horses. photo credit: James Watts

On location for the re-enactment of The Hay Wain at Flatford Mill, Suffolk. photo credit: Pipi Lovell-Smith

Re-enactment of The Hay Wain at Flatford Mill, Suffolk. Mark Battie. photo credit: James Watts

Re-enactment of The Hay Wain at Flatford Mill, Suffolk. N&J Heavy Horses. photo credit: James Watts

Re-enactment of The Hay Wain at Flatford Mill, Suffolk. Theresa Burton. photo credit: Pipi Lovell-Smith

Cat Auburn & Estella Castle (2016). Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay. film still

Cat Auburn & Estella Castle (2016). Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay. film still

Canterbury is 100, film still, photo credit: Archives New Zealand

The following text is by New Zealand curator, Sarah McClintock

“Painting is with me but another word for feeling”

John Constable, in a letter to the Rev. John Fisher, Hampstead, 23 October 1821

In 1816, under the soft light of the early summer sun and as a warm breeze carried the sweet smell of elderflowers, John Constable sketched drawings that would later become his iconic painting, The Hay Wain. In 1821 the six foot work was finished in Constable’s London studio, using his vast collection of reference drawings to carefully construct a perfect view of rural life.

Willy Lott’s Cottage, which the painting depicts, has undergone many changes over the centuries since Constable first sketched the site. To commemorate the 200th anniversary of Constable’s time in Suffolk contemporary artist’s Estella Castle and Cat Auburn recreated The Hay Wain at the original site. On 4 September 2016, the artists careful art directed the restaging of this iconic British painting. The result of the day was not simply a faithful reproduction of the painting but a video work that examines the roles of distance, influence, pilgrimage, authenticity and recreation in historic and contemporary art.

The title for this exhibition comes from the 1956 book ‘Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay’ by George Ewart Evans. Conducted as an oral history, Evans recorded the recollections, tales and customs of the people of rural Suffolk. Deeply rooted in nostalgia for the ‘old’ ways of farming and living as a community, working the land with their hands, this book captures the same wistful desires expressed by Constable’s The Hay Wain. The individuals Evans interviewed were real people who worked hard during trying times. The Hay Wain depicts a real place where real farming was conducted. Both capture something that is lost, and its disappearance represents a deep cultural, economic and political shift in Britain’s history. The irony of this title is that hay was excluded from the recreation. Now absent from the cart and back fields, it is through its removal that the aritsts ellude to the reframing of the site overtime from a place of agriculature to a place of culture.

When Constable was painting The Hay Wain Britain was on the cusp of the Industrial Revolution. The type of idyllic agrarian labour depicted in the painting was about to become mechanised. It is this transformation of how the land was cultivated that has been a factor in the rise of The Haywain as one of Britain’s most beloved painting. It freezes in time a less complicated life. The question becomes – given Constable’s practice as an artist is this romantic view of Suffolk accurate? Landscape paintings are ‘a natural scene mediated by culture’.[1] No painting can be perfectly accurate because they are filtered through the artist’s eye. Did Constable every see a team of horses in the pond while a woman was washing clothing? He almost certainly didn’t but fidelity was not the point of this painting – it was spirit.

The fluidity of authenticity is crucial to Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay. The goal of any recreation is to create an almost perfect facsimilia of the original. But perfection is an impossible goal. Instead the recreation becomes about the slippages and what that reveal about the original. The most recognisable example of this is the inability to locate the horses and cart within the pond. It is far too deep to safely drive a team of horses into its waters. Thes site is no longer a functioning mill and without the constant flow of water silt has settled in the pond, making it impoossible to safely take horses into its depths. Instead of being perturbed by the impossibilities the artists instead viewed them as opportunities to interrogate the role of authenticity in art. The land wasn’t pristine before and during Constable’s lifetime. Agriculture leaves scars on nature and in New Zealand, as well as England, native forests and bush have been destroyed to make way for cultivation. A perfect landscape may not exist but the impossibilities of the painting make it no less impactful as a record of a privileged view of rural history.

It is impossible to ignore that the artists responsible for this recreation of a very British work are in fact New Zealanders. New Zealand/Aotearoa is as far away from England as you can possible get. There are 18,695 km or 11,617 miles between the two countries. Growing up in this colonial nation we were taught that ‘real’ art was something that existed on the other side of the world. Printed reproductions of paintings by the great British and European masters were hung above fireplaces in countless antipodean homes as examples of our heritage.

The first paintings of New Zealand were completed in England; official artists accompanied Captain James Cook on his voyages to the South Pacific with the purpose of capturing in paint the wonders they witnessed during these ambitious expeditions. With the colonisation of New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century the British lens with which the county was viewed was solidified. Despite the obvious differences in light and landforms, early painters of New Zealand imposed a European understanding of the landscape in the work created in this ‘new’ country. High culture was percieved as the purview of Europe and Britain and New Zealanders were to learn at their feet.

Constable’s work is embued with the issues of temporal and physical distance. His initial sketches for the painting that would come to be known as The Hay Wain can be dated to 1810-1816, a full decade before the canvas was complete. The preparatory studies were made during his many visits to his home county of Suffolk, but the final work was completed in his London studio. He felt “I should paint my own places best… I associate ‘my careless boyhood’ with all that lies on the banks of the Stour; those scenes made me a painter, and I am grateful.”[2]

By working and living in Britain Auburn and Castle are supremely conscious of the tension that exists between distance and culture. By recreating this icon of British landscape painting they are exorcizing the past and reclaiming distance as a way to give perspective to the dominant cultural narratives that continue to pull New Zealanders back to Britain. With their awareness of the ubiquitousness of a British framework of understanding within the nations that once formed the British Empire, the artists, by injecting a New Zealand presence within The Hay Wain are performing their own kind of colonisation.

Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay exists as two intertwined artworks. One being the recreation as an event: the day when the artists, horses, cart, dog, actors, and audience converged to restage The Haywain. This all or nothing day, where anything could and did happen, was equally ambitious and unpredictable. The second work is the result of the day – a video created with footage from the day, both shot by the artists and the audience, positioned beside real and restaged archival footage of English and New Zealand landscapes. Britain’s influence on the way in which New Zealand has historically viewed itself is given a literal voice with the inclusion of the archival footage from both England and New Zealand. The strikingly similar presentations mirror the cultural influence of ‘Home’ on this small British outpost. Until the mid-twentieth century England was ‘Home’ for Pākehā (the Māori word for New Zealanders of European descent). This multi-generational sense of belonging somewhere else, with a cultural heritage across a vast ocean, is what draws many antipodeans to England.

Despite the proliferation of Hay Wain merchandise across the world people still feel the draw to visit the painting itself, on permanent display at The National Gallery in London, and to Willy Lott’s Cottage in Flatford. Much like the regular trips Constable himself made, each year thousands of people make the pilgrimage to ‘Constable Country’. Visitors throng to this beautiful part of Suffolk in an attempt to get closer to the artist, and perhaps transport themselves, even if only for a moment, to his time. Walking where he walked, seeing what he saw – the longing for this type of connection to a historical figure is universal and drives a significant amount of cultural tourism. By actively encouraging visitors to come to Flatford to view the recreation Auburn and Castle were engaging this act of pilgrimage to facilitate and furnish this dual artwork.

The drama of the recreation is distilled through the camera’s lens, much in the same way Constable art directed his large scale canvases. While he sketched directly from nature the final view was carefully constructed with different skies, carts and animals constructed to create the ideal country science. But not necessarily the truth.

[1] W.J.T. Mitchell, ‘Imperial Landscape’ in W.T. Mitchell (ed), Landscape and Power, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994, p. 5.

[2] John Constable, in a letter to the Rev. John Fisher, Hampstead, 23 October 1821

An interview by Lynn Freeman with Cat Auburn and Sarah McClintock. Radio New Zealand, Standing Room Only – Constable’s Hay Wain – live! 7 August 2016

An interview with Estella Castle on BBC Suffolk Radio 17 August 2016

FULL PRODUCTION CREDITS:

ASK THE FELLOWS WHO CUT THE HAY

CAT AUBURN & ESTELLA CASTLE

Narrator ROSANNA ARBON

Cart Driver NEIL KITCHEN

Farmer in Cart GINA HACKLING

Fisherman in Boat MARK BATTY

Washer Woman THERESA BURTON

Spaniel ELLIE

Horse Handlers

JULIA KITCHEN

SAM DEAN

Dog Handler RICHARD MILLER

Shire Horses supplied by

N&J HEAVY HORSES

Project Consultant BEN PIPE

Curatorial Researcher SARAH MCCLINTOCK

Painting and Site Researcher ESTELLA CASTLE

Painting Conservation Advisor ALEX OWEN

Creative Producer DAN SLAUGHTER

Directors

CAT AUBURN

ESTELLA CASTLE

Assistant Director PIPI LOVELL-SMITH

Camera Operators

DAN SLAUGHTER

GRACE DENTON

TIM CROFT

Sound Recordist JAMES WATTS

Production Assistants

BEN ISAACS

SARAH MCCLINTOCK

HAYLEY MCCONNELL

JASON SEABROOK

Editor CAT AUBURN

Stills Photographer JAMES WATTS

Catering JASON SEABROOK

Costumes supplied by

EASTERN ANGLES THEATRE COMPANY

WEALD AND DOWNLAND OPEN AIR MUSEUM

NATIONAL TRUST ESSEX

SAMANTHA WHETTON

SIMON STACHE

Boat supplied by DOMINIC GRANT of FLATFORD BOAT HIRE

Cart supplied by N&J HEAVY HORSES

Decoy ducks supplied by FARLOWS

Christchurch is A Hundred (1950)

courtesy of ARCHIVES NEW ZEALAND

Narrated Excerpts

The Hay Wain Conservation Dossier NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON

Ask the Fellows Who Cut the Hay GEORGE EWART EVANS

The Hay Wain, A Constable View Conservation Plan

NATIONAL TRUST FLATFORD

Location FLATFORD SUFFOLK

Made with the Support of the National Trust, Flatford, Suffolk

The Artists Wish to Thank

NATIONAL TRUST FLATFORD

NATIONAL TRUST ESSEX

ARCHIVES NEW ZEALAND Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

THE SUTER ART GALLERY Te Aratoi o Whakatu

FIELD STUDIES COUNCIL FLATFORD MILL

BBC SUFFOLK

NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY

TYNESIDE CINEMA

BEN PIPE · SIMON PEACHEY

NEIL & JULIA KITCHEN

HANNAH & RICHARD MILLER